At some point during the first session of Professor Steve Herbert’s seminar course on law, societies and justice this fall, a change worked its way over those sitting in the beige meeting room being used as a classroom.

The 11 University of Washington students began to realize that their fellow students — 10 prisoners serving time in the Washington State Reformatory — were every bit as prepared for the class as they were.

Maybe more so.

After the UW students walked out of the Monroe prison, “I remember … mostly what they said is, ‘These guys are smart. They had done the reading. Oh my gosh, this is going to be a challenging intellectual experience,’ ” Herbert said.

It’s the third time Herbert, a past winner of the UW’s distinguished teaching award, has taught a “mixed-enrollment” class at the reformatory — half the class made up of UW students, the other half inmates.

“The biggest surprise is how normal the actual class and experience feels,” Herbert said. “It’s every bit as robust and engaged a conversation as I’ve had in any classroom, on or off campus, and it’s been very easy to create a strong classroom dynamic.”

Many of Herbert’s students would go one step further.

Debating criminal-justice policies with inmates has stretched Nathan Bean’s understanding of the system in ways that would have been impossible in the relatively homogeneous UW-Seattle setting.

“Every week, there were statements and claims that I could just never get on the UW campus,” said Bean, who at 38 has returned to college to get a degree in law, societies and justice.

Fellow classmate Kathryn Joy said learning from people who are incarcerated “shattered some of my own preconceptions — what transpires in prison, what it’s like to come into contact with the law.” She is a senior majoring in law, societies and justice.

The inmates have “really forced me to consider the fundamentals of this institution (prison), and the fundamentals of law and justice completely,” said Hannah Schwendeman, also a senior majoring in law, societies and justice.

Logistical challenge

The class is taught in partnership with University Beyond Bars, a nonprofit that provides college-prep and college-level courses at the Washington State Reformatory and the Minimum Security Unit, both in Monroe.

It comes at a time when both conservatives and liberals are considering changes in the criminal-justice system, including reinstating parole and reviewing the length of prison sentences. The United States has the highest prison population rate in the world; about 716 of every 100,000 people are in prison.

When state lawmakers reconvene in January, they will consider a bill that would lift the prohibition on using state tax money to provide academic classes in prison, something that’s been disallowed since 1995.

Studies show that inmates who earn college degrees have lower rates of recidivism, said Marty Brown, executive director of the State Board for Community and Technical Colleges. The state community-college system already runs vocational classes in prison and could offer academic classes, as well, if they were allowed, Brown said.

Herbert said he sought to teach a class in prison because, although discussing mass incarceration in a college classroom is valuable, “it’s something else entirely to meet an actual prisoner, and get a more immediate sense of what the experience of punishment is like.”

The class was something of a logistical challenge, one that involved getting 11 students up to Monroe 10 times over the quarter, and going through identity checks, searches and security barriers.

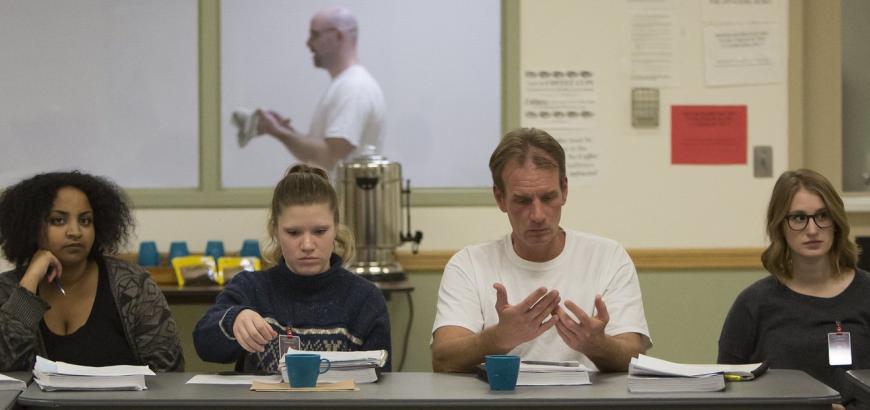

But once the UW students moved past the sliding steel gates and the guard station, through the inner courtyard and its razor-wire-topped fence, they sat in a classroom that seemed like any other — save for the fact that their classmates were dressed in gray and beige prison-issued clothes, and armed guards walked the hallways.

One day this month, the last day of the course, the UW students and the prison inmates greeted each other warmly before class began. They poured strong cups of coffee from an urn and unpacked their reading materials onto tables. After some guidance from Herbert about the day’s topic — restorative justice — they broke up into small group discussions.

Schwendeman, who had been to Monroe previously as part of research project on parole, said she welcomed the chance to take a college course with people who have had such different life experiences.

“We get a very particular image of who a criminal is,” she said. “Going into that institution, shaking their hands, seeing their faces, you realize how much of a lie that is. We’re incarcerating people with aspirations, knowledge, ideas, stories. I think that piece is very often forgotten.”

Different view

The prisoners didn’t earn college credit because the UW would need to charge them for a credit-bearing class, and most could not afford it, Herbert said.

But the inmates were often some of the most thoughtful voices during discussions, and usually read every word of the assigned reading, the students said. (“We have a lot of time,” one inmate said, wryly.)

Noel Caldellis has taken all three of Herbert’s classes. “I think it’s very clear, from the way Professor Herbert does this class and the larger discussion, the students are, ‘Wow, these guys are really good — they know what they’re talking about,’ ” he said.

Caldellis, who entered prison without any college credit, has earned an associate degree through University Beyond Bars. He’s now working on his bachelor’s in history.

He was convicted of first-degree murder in 2008, and his scheduled release date is in 2029.

Devon Adams, who is serving time for first-degree murder, says he tries to make the most of educational opportunities. He’s taken two of Herbert’s classes, and is earning his bachelor’s degree via correspondence courses through Ohio University. He is two courses shy of his bachelor’s degree, and is working to set a good example for his daughter, a high-school student who wants to go to the UW.

Of the opportunity to get an education, “some would say we don’t deserve it,” Adams said. “I can’t argue with that.”

But he said he hoped to give the UW students a different view of prison. “I think, in our culture, there is an image of what a prisoner is, and we can provide some perspective,” he said. “Maybe that’s one way we can give back to our community.”

He was convicted in 2000 of killing a man in South Seattle after an argument, and is scheduled to be released in 2024.

During the class, Bean, the UW student, said he came to regard the inmates as “not just prisoners, but students. And damn good students” — men who challenged his own understanding of mass incarceration.

Those ideas have made Bean think about the consequences of putting so many people in prison, and how punishment could change.

For example, he said, instead of building solitary-confinement cells, which are expensive, why not use that money to offer inmates a college education?

“Why not?” he asked. “Why is that crazy? Twenty or thirty years ago, you would have been laughed out of the room. For me, it doesn’t sound that crazy anymore.”